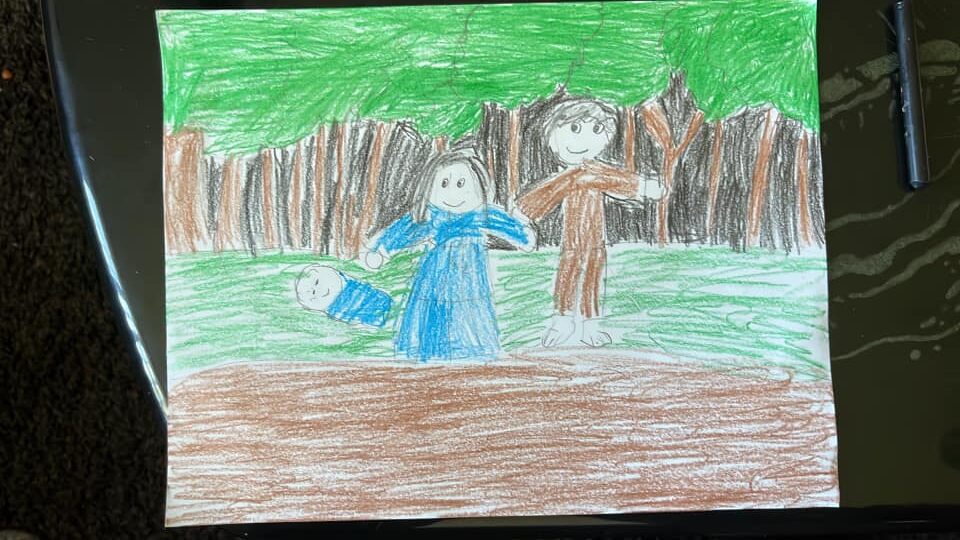

During the Buddha’s life, a rich lady fell in love with a poor man, and to avoid trouble from lady’s parents they ran away from home and settled elsewhere. When the lady was going to give birth to her first child, she decided to go back home, but she didn’t reach home on time and gave birth to her baby-boy on the road. The same thing happened also with her second child, also a boy. Both of them were therefore called “Panthaka” (“from the road”), the first one Mahāpanthaka (big Panthaka) and the second Cūḷapanthaka (small Panthaka). The children wanted to see their grandparents, so their parents agreed. The grandparents were not willing to accept the mother and father of their grandchildren, but they sent them money and took responsibility for the grandchildren. Mahāpanthaka went to listen to Dhamma together with his grandfather, and later asked his grandfather, a follower of the Buddha, for permission to become a monk. With the permission he became a novice and later fully ordained monk. As a monk he memorized many scriptures and also meditated until he became an Arahant (fully Enlightened). Happy about the success, he encouraged his younger brother Cūḷapanthaka to become a monk too. Cūḷapanthaka, however, was not able to memorize even a single verse during four months of learning.

The reason for this failure was that in his past life, Cūḷapanthaka was a monk who had a lot of knowledge and then laughed to despise a dull monk who tried to memorize the Buddha’s Teachings. This despising and scorning confused the fellow monk, who then was not able to memorize anything. That is why now, in the life during the Buddha Gotama, he is a dullard.

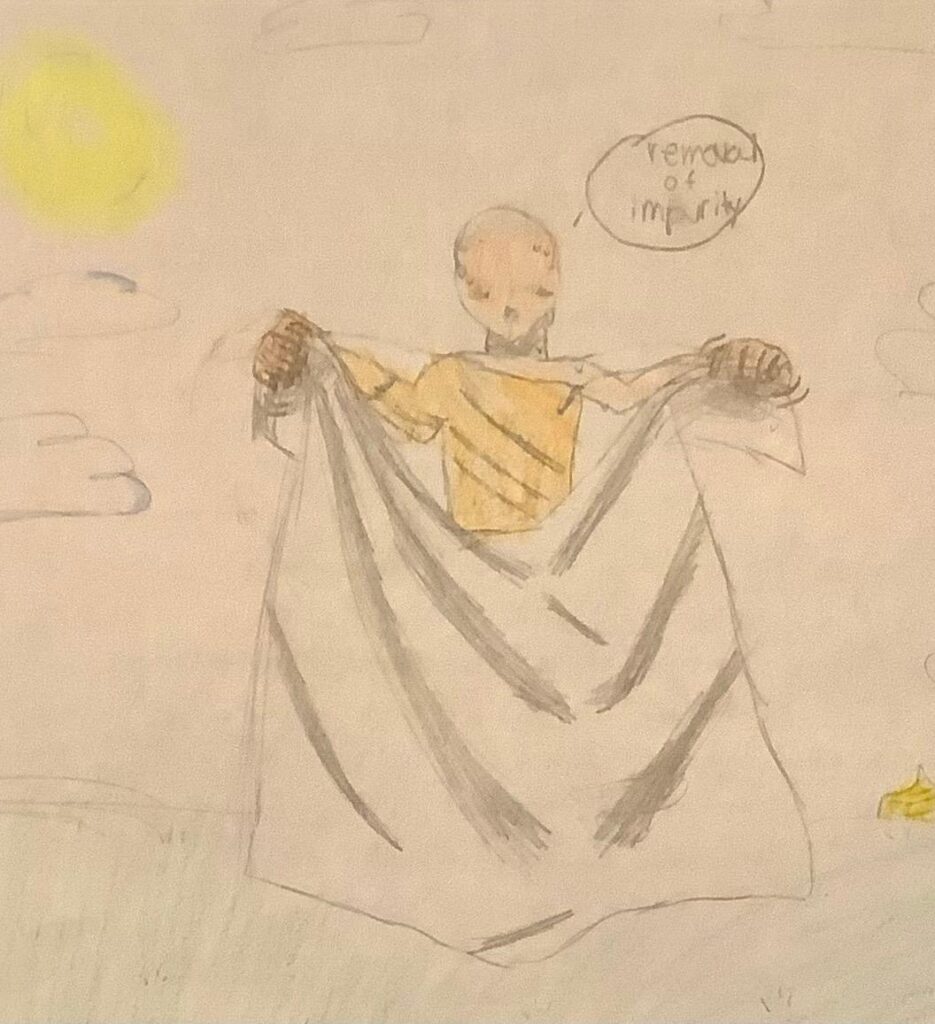

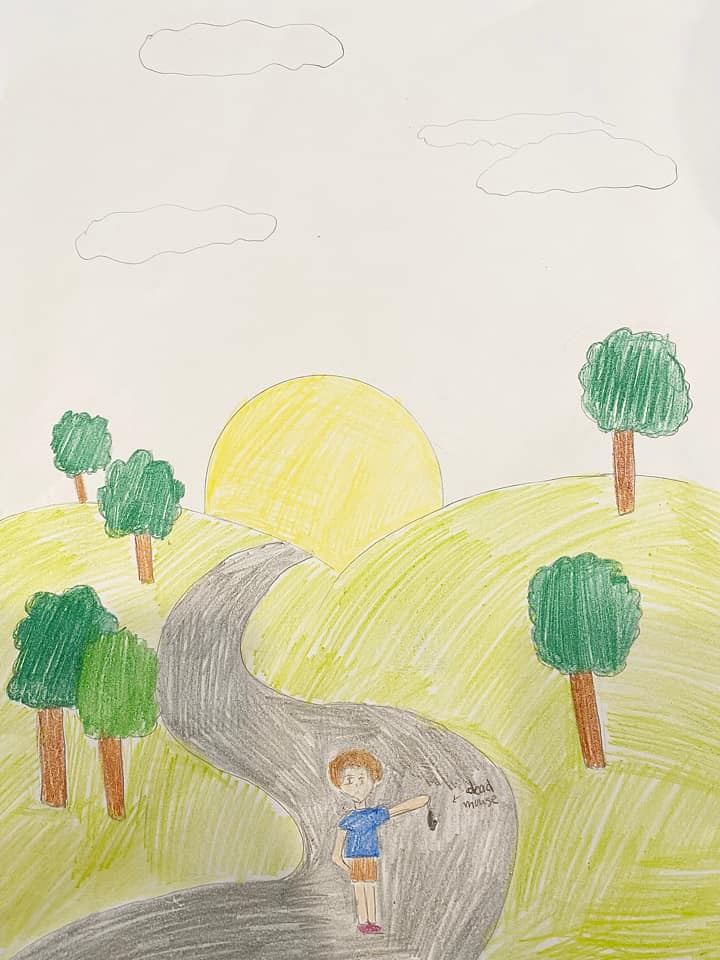

His elder brother Mahāpanthaka then decided that Cūḷapanthaka is not suitable for monkhood and expelled him from the monastery. On the way home, Cūḷapanthaka was stopped by the Buddha and received a meditation instruction of observing a white cloth and meditating on impermanence. The young monk then rubbed the cloth and repeated “removal of impurity, removal of impurity”. He noticed the cloth got dirty by his rubbing and fully understanding the impermanent nature of all things, he achieved the first level of Enlightenment right then and there. The Buddha, while accepting a meal in a donor’s house, made an illusion of Himself to appear right in front of the meditating Cūḷapanthaka. The Buddha explained, that real impurity is greed, hatred, ignorance, and that removing them from one’s heart will result in stainless life in accordance with the Buddha’s Teachings. Right after the admonishment Cūḷapanthaka achieved the highest level of Enlightenment (Arahanthood) together with extraordinary wisdom, knowledge, and psychic powers.

Cūḷapanthaka was able to achieve Enlightenment so fast because already in a past life, when he was a king, one day during a procession in his city he noticed his clothes got dirty by the sweat that escaped from his body. He thought: “It is this body of mine which has destroyed the original purity and whiteness of the cloth, and dirtied it. Impermanent indeed are all composite things.”

Now at that time Mahāpanthaka was acting as steward. And Jīvaka Komārabhacca, going to his mango-grove with a large present of perfumes and flowers for the Teacher, had presented his offering and listened to a discourse; then, rising from his seat and bowing to the One with Ten Powers, he went up to Mahāpanthaka and asked, “How many monks are there, venerable sir, with the Teacher?” “Just 500, sir.” “Will you bring the 500 monks, with the Buddha at their head, to take their meal at my house tomorrow?” “Lay disciple, one of them named Cullapanthaka is a dullard and makes no progress in the Faith,” said the elder, “I accept the invitation for everyone but him.”

Jīvaka Komārabhacca offered the Water of Donation; but the One with Ten Powers [the Buddha] put his hand over the vessel, saying: “Are there no monks, Jīvaka, in the monastery?” Said Mahāpanthaka, “There are no monks there, venerable sir.” “Oh yes, there are, Jīvaka,” said the Teacher. “Hi, there!” said Jīvaka to a servant, “just you go and see whether or not there are any monks in the monastery.” At that moment Cullapanthaka, conscious as he was that his brother was declaring there were no monks in the monastery, determined to show him there were, and so filled the whole mango-grove with nothing but monks. Some were making robes, others dyeing, while others again were repeating the sacred texts: each of a thousand monks he made unlike all the others. Finding this host of monks in the monastery, the man returned and said that the whole mango-grove was full of monks.

But as regards the elder up in the monastery –

“Panthaka, a thousand-fold self-multiplied,

Sat on, till bidden, in that pleasant grove.”

“Now go back,” said the Teacher to the man, “and say ‘The Teacher sends for him whose name is Cullapanthaka.’ ”

But when the man went and delivered his message, a thousand mouths answered, “I am Cullapanthaka! I am Cullapanthaka!” Back came the man with the report, “They all say they are ‘Cullapanthaka,’ venerable sir.”

“Well now go back,” said the Teacher, “and take by the hand the first one of them who says he is Cullapanthaka, and the others will all vanish.” The man did as he was requested, and straightaway the thousand monks vanished from sight. The elder came back with the man. When the meal was over, the Teacher said: “Jīvaka, take Cullapanthaka’s bowl; he will return thanks.” Jīvaka did so. Then like a young lion roaring defiance, the elder ranged over the whole of the sacred texts through in his address of thanks. Lastly, the Teacher rose from his seat and attended by the Saṅgha returned to the monastery, and there, after the assignment of tasks by the Saṅgha, he rose from his seat and, standing in the doorway of his perfumed chamber, delivered a Sugata’s discourse to the Saṅgha. Ending with a theme which he gave out for meditation, and dismissing the Saṅgha, he retired into his perfumed chamber, and lay down lion-like on his right side to rest.

At evening, the orange-robed monks assembled together from all sides in the Dhamma Hall and sang the Teacher’s praises, even as though they were spreading a curtain of orange cloth round him as they sat. “Monks,” it was said: “Mahāpanthaka failed to recognise the character of Cullapanthaka, and expelled him from the monastery as a dullard who could not even learn a single verse in four whole months. But the All-Knowing Buddha by his supremacy in the Dhamma bestowed on him Arahatship with all its supernatural knowledge, even while a single meal was in progress. And by that knowledge he grasped the whole of the sacred texts. Oh! How great is a Buddha’s power!”

Now the Fortunate One, knowing full well the talk that was going on in the Dhamma Hall, thought it good to go there. So, rising from his Buddha-couch, he donned his two orange robes, girded himself as with lightning, arrayed himself in his upper robe, the ample robe of a Buddha, and came forth to the Dhamma Hall with the infinite grace of a Buddha, moving with the royal gait of an elephant in the plenitude of his vigour. Ascending the glorious Buddha-throne set in the midst of the resplendent hall, he seated himself upon the middle of the throne emitting those six-coloured rays which mark a Buddha – like the newly-arisen sun, when from the peaks of the Yugandhara Mountains he illumines the depths of the ocean. Immediately the Buddha came into the Hall, the Saṅgha broke off their talk and were silent. Gazing round on the company with gentle loving-kindness, the Teacher thought within himself, “This company is perfect! Not a man is guilty of moving a hand or foot improperly; not a sound, not a cough or sneeze is to be heard! In their reverence and awe of the majesty and glory of the Buddha, not a man would dare to speak before I did, even if I sat here in silence all my life long. But it is my part to begin; and I will open the conversation.”

Then in his sweet divine tones he addressed the monks and said, “What, pray, is topic of this meeting? And what was the talk which was broken off?” “Sir,” they said, “it was no profitless theme, but your own praises that we were telling here in a meeting.” And when they had told him word for word what they had been saying, the Teacher said: “Monks, through me Cullapanthaka has just now risen to great things in the Dhamma; in times past it was to great things in the way of wealth that he rose – but equally through me.”

The monks asked the Teacher to explain this; and the Fortunate One made clear in these words a thing which succeeding existences had hidden from them: /

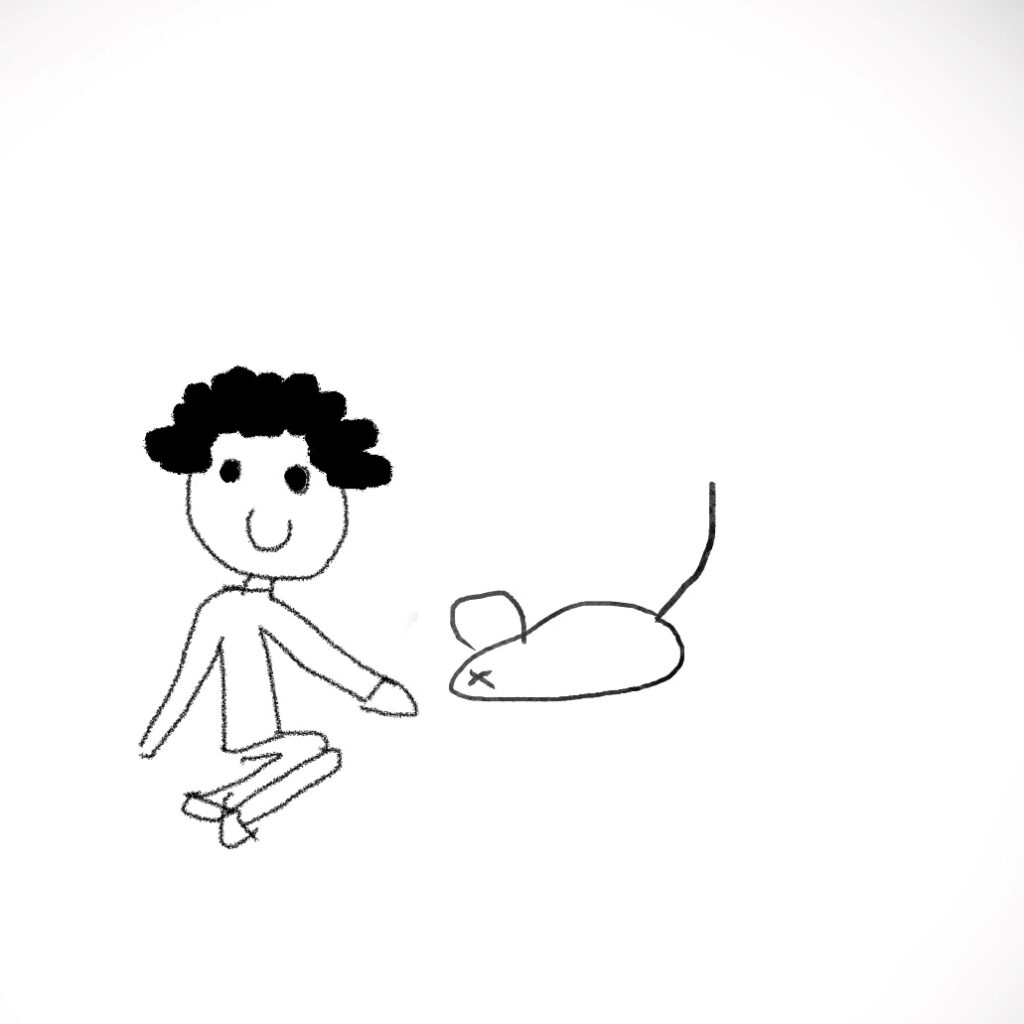

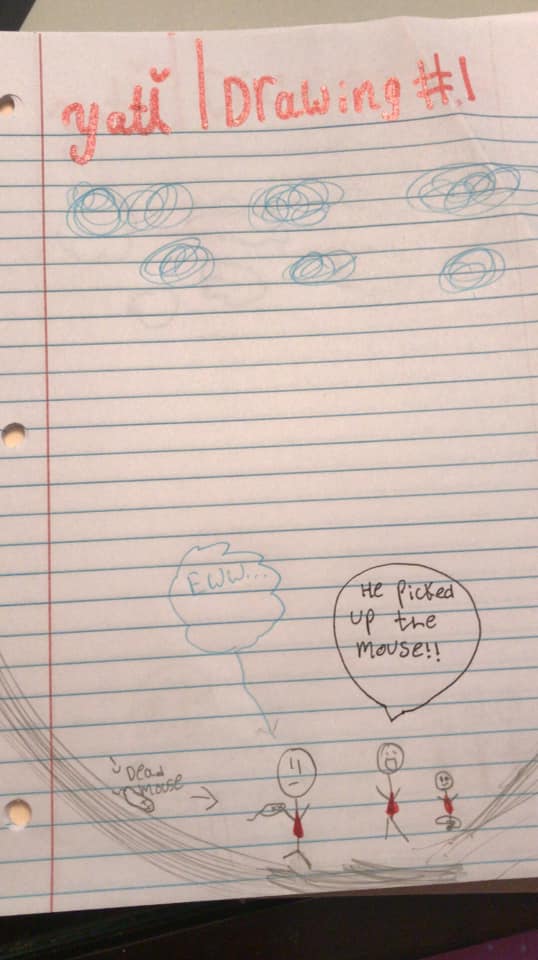

In the past when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares in Kāsi, the Bodhisatta was born into the Treasurer’s family, and growing up, was made Treasurer, being called Cullakaseṭṭhi. A wise and clever man was he, with a keen eye for signs and omens. One day on his way to wait upon the king, he came on a dead mouse lying on the road; and, taking note of the position of the stars at that moment, he said: “Any decent young fellow with his wits about him has only to pick that mouse up, and he might start a business and keep a wife.” His words were overheard by a young man of good family but reduced circumstances, who said to himself, “That’s a man who has always got a reason for what he says.” And accordingly he picked up the mouse, which he sold for a quater-penny at a tavern to feed their cat.

With the quater-penny he got molasses and took drinking water in a waterpot. Coming on flower-gatherers returning from the forest, he gave each a tiny quantity of the molasses and ladled the water out to them. Each of them gave him a handful of flowers, with the proceeds of which, next day, he came back again to the flower grounds provided with more molasses and a pot of water. That day the flower-gatherers, before they went, gave him flowering plants with half the flowers left on them; and thus in a little while he obtained eight pennies. Later, one rainy and windy day, the wind blew down a quantity of rotten branches and boughs and leaves in the king’s pleasure gardens, and the gardener did not see how to clear them away. Then up came the young man with an offer to remove the lot, if the wood and leaves might be his. The gardener closed with the offer on the spot. Then this apt pupil of Cullakaseṭṭhi repaired to the children’s playground and in a very little while had got them by bribes of molasses to collect every stick and leaf in the place into a heap at the entrance to the pleasure gardens. Just then the king’s potter was on the look out for fuel to fire bowls for the palace, and coming on this heap, took the lot off his hands. The sale of his wood brought in sixteen pennies to this pupil of Cullakaseṭṭhi, as well as five bowls and other vessels.

Having now twenty-four pennies in all, a plan occurred to him. He went to the vicinity of the city-gate with a jar full of water and supplied 500 mowers with water to drink. They said: “You’ve done us a good turn, friend. What can we do for you?” “Oh, I’ll tell you when I want your aid,” said he; and as he went about, he started a friendly talk with a land-trader and a sea-trader. Said the former to him, “Tomorrow there will come to town a horse-dealer with 500 horses to sell.” On hearing this piece of news, he said to the mowers, “I want each of you today to give me a bundle of grass and not to sell your own grass till mine is sold.”

“Certainly,” they said, and delivered the 500 bundles of grass at his house. Unable to get grass for his horses elsewhere, the dealer purchased our friend’s grass for a thousand pieces.

Only a few days later his sea-trading friend brought him news of the arrival of a large ship in port; and another plan struck him. He hired for eight pence a well appointed carriage which plied for hire by the hour, and went in great style down to the port. Having bought the ship on credit and deposited his signet-ring as security, he had a pavilion pitched nearby and said to his people as he took his seat inside, “When merchants are being shown in, let them be passed on by three successive ushers into my presence.” Hearing that a ship had arrived in port, about a hundred merchants came down to buy the cargo; only to be told that they could not have it as a great merchant had already made a payment on account. So away they all went to the young man; and the footmen duly announced them by three successive ushers, as had been arranged beforehand. Each man of the hundred severally gave him a thousand pieces to buy a share in the ship and then a further thousand each to buy him out altogether. So it was with 200,000 pieces that this pupil of Cullakaseṭṭhi returned to Benares. Actuated by a desire to show his gratitude, he went with one hundred thousand pieces to call on Cullakaseṭṭhi. “How did you come by all this wealth?” asked the Treasurer. “In four short months, simply by following your advice,” replied the young man; and he told him the whole story, starting with the dead mouse. Thought the Lord High Treasurer Cullakaseṭṭhi, on hearing all this, “I must see that a young fellow of these parts does not fall into anybody else’s hands.” So he married him to his own grown-up daughter and settled all the family estates on the young man. And at the Treasurer’s death, he became Treasurer in that city. And the Bodhisatta passed away to fare according to his deeds. His lesson ended, the Supreme Buddha, after Fully Awakening, repeated this

verse:

1. “With humblest start and trifling capital

A shrewd and able man will rise to wealth,

Even as his breath can nurse a tiny flame.”

Also the Fortunate One said: “It is through me, monks, that Cullapanthaka has just now risen to great things in the Faith, as in times past to great things in the way of wealth.” His lesson thus finished, the Teacher made the connection between the two stories he had told and identified the Jātaka in these concluding words, “Cullapanthaka was in those days the pupil of Cullakaseṭṭhi, and I myself the Lord High Treasurer.”

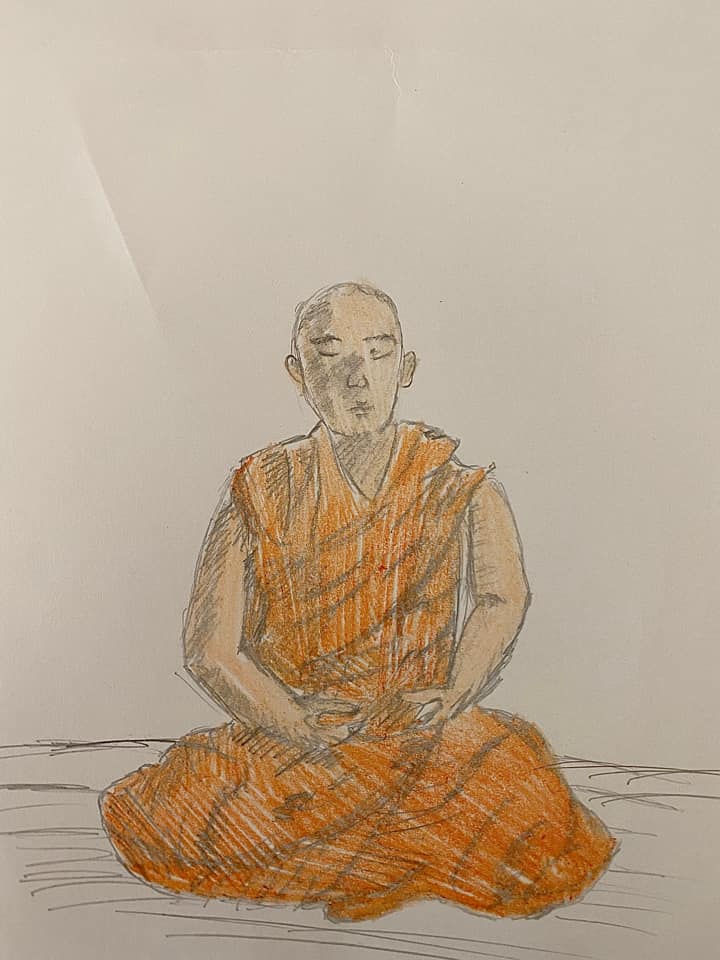

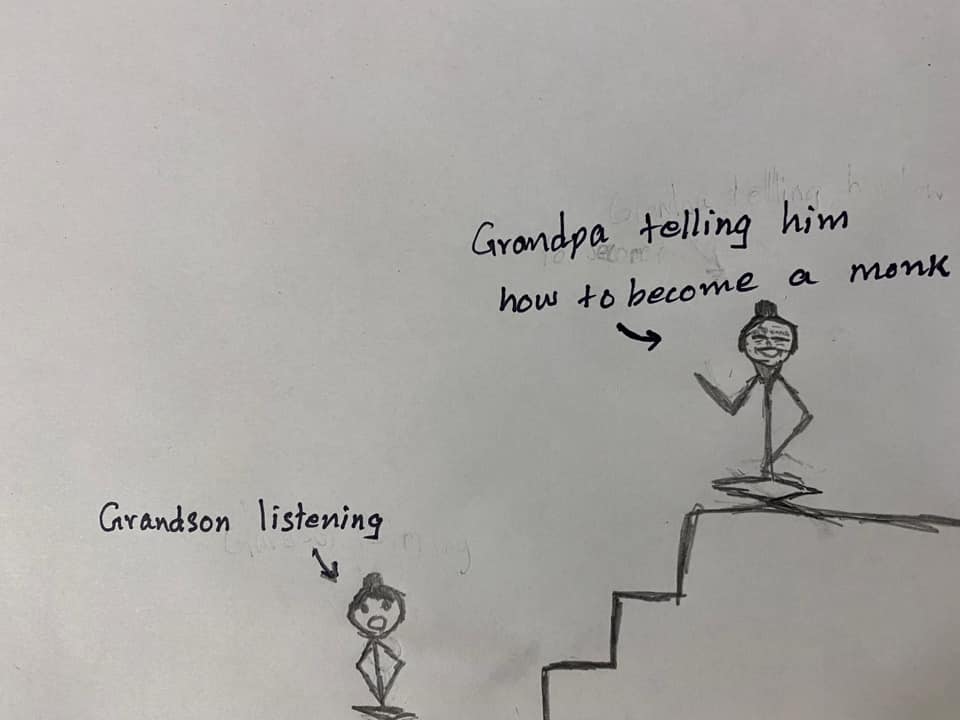

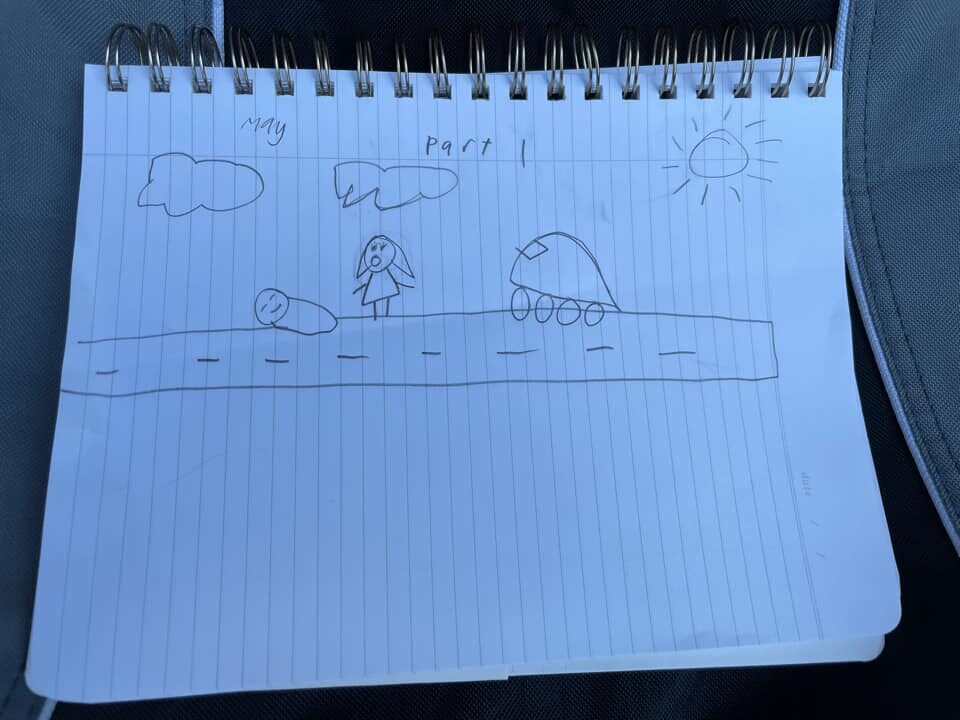

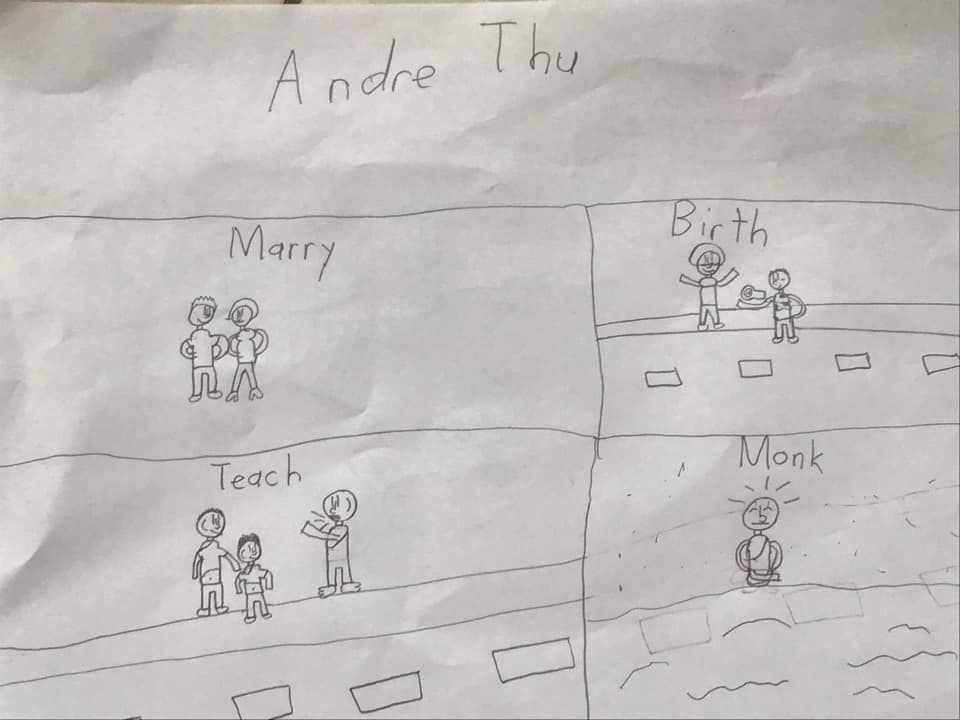

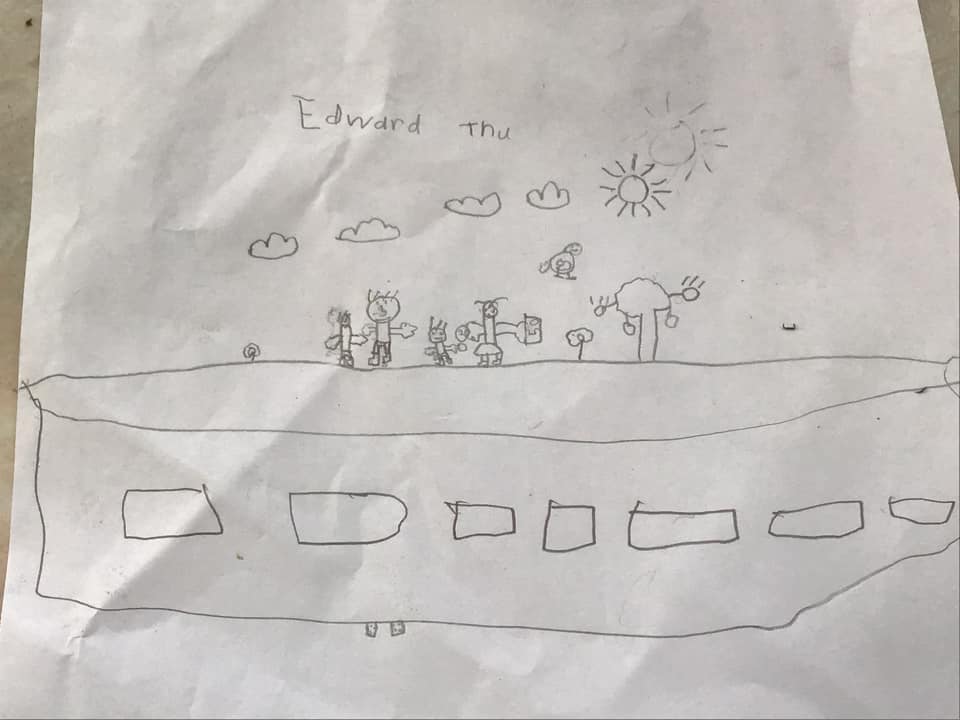

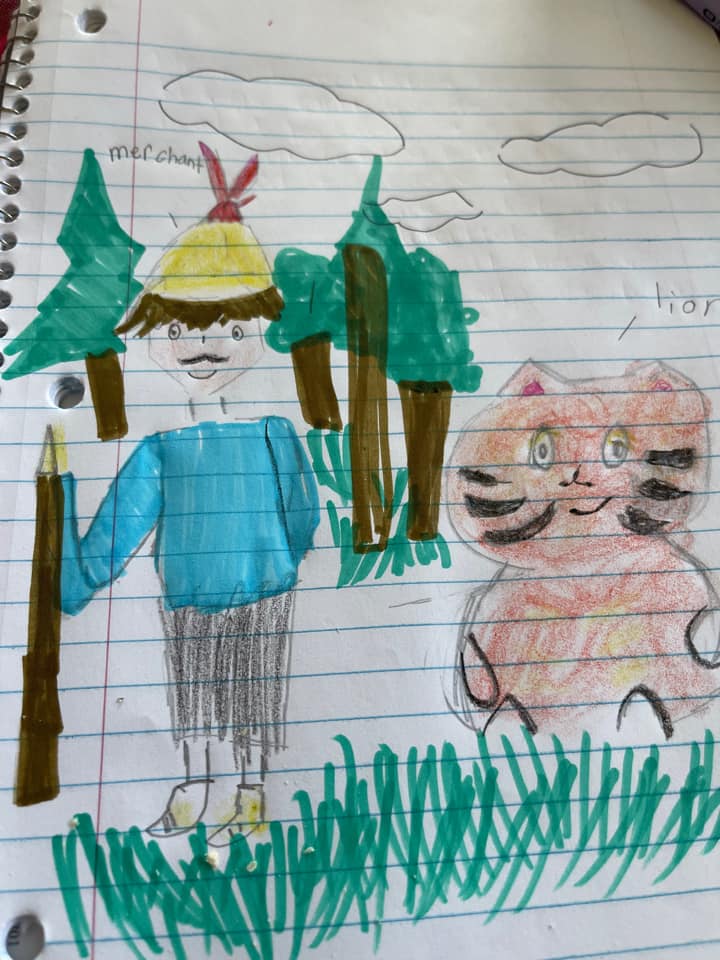

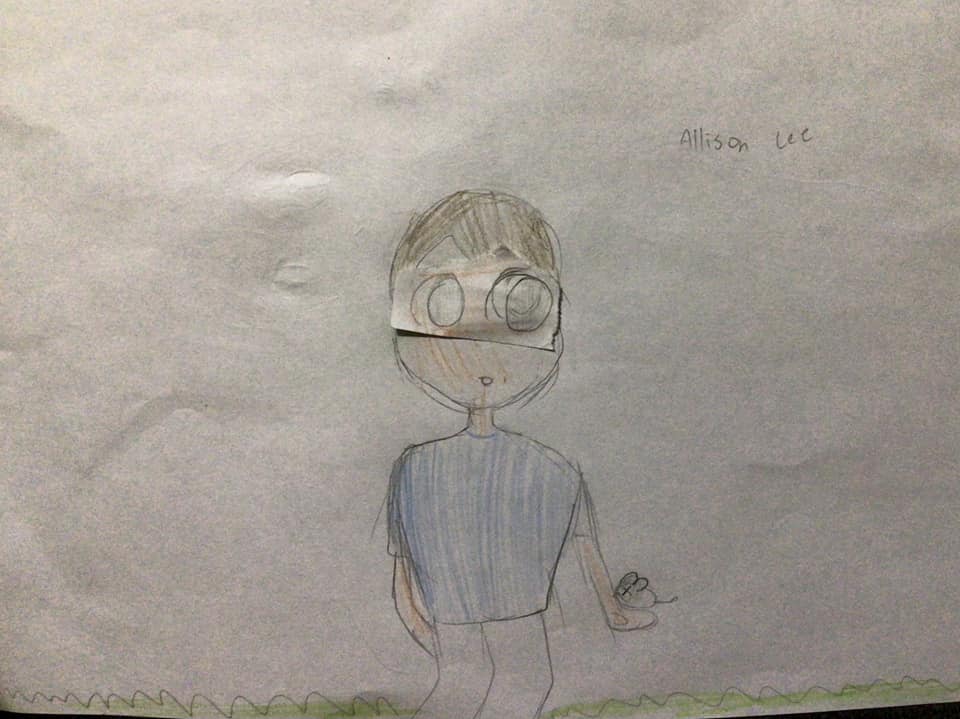

Suggestions for drawing:

A baby-boy born on a road, old man with his grandson listening to Dhamma teachings from the Buddha, a young monk meditating, a monk sitting in front of another monk and repeating the Teachings, a young monk going home and meeting the Buddha on the way, a young monk holding a white cloth and rubbing it with his fingers.

A monastery filled with young monks doing various activities (sweeping, teaching, learning, meditating, washing things), a young man who picks up a mouse, a young man giving palm sugar (sugar balls) and water to farmers, a garden with a lot of trees fallen, a young man on a boat, and anything else that is mentioned in the story.

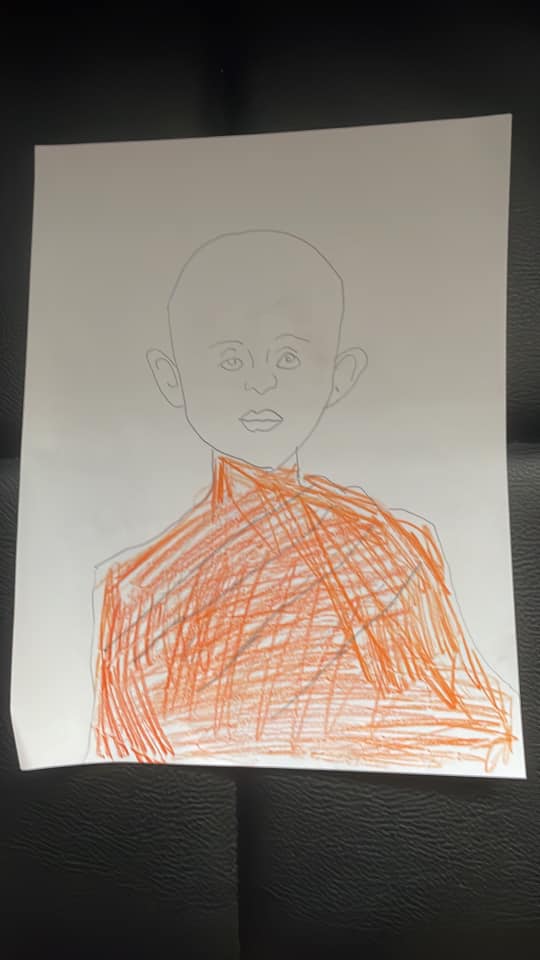

Picture for inspiration: a novice studying Buddhist scriptures (In the Buddha’s time, however, monks and novices did not have books to study from; they had to memorize the Teachings by listening to it as their teachers repeated it again and again – the picture here contains chronological contradiction, it is “asynchronous”.)

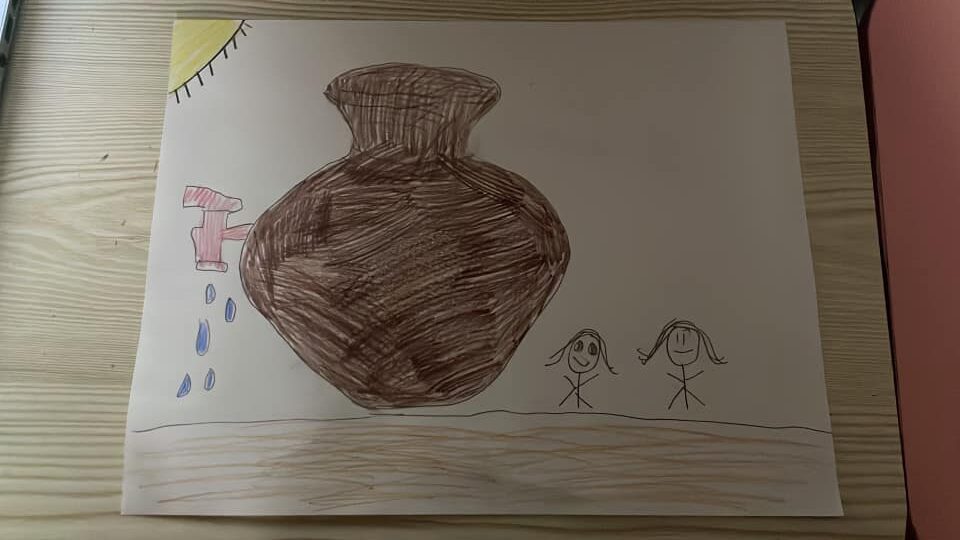

Picture for inspiration: Myanmar water-pot (yay-oh) that is kept by the side of roads and paths so that thirsty people can easily drink and refresh themselves.

Jātakas – The Jātaka Translation or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births (pages 161-167) – T.W. Rhys Davids, R. Chalmers, H.T. Francis, W.H.D. Rouse, E.B. Cowell, revised Ānandajoti Bhikkhu, 2021(1880) (2964p), with some of the old words changed into new words by Ashin Saraṇa.

Jātakas – The Jātaka Translation or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births – T.W. Rhys Davids, R. Chalmers, H.T. Francis, W.H.D. Rouse, E.B. Cowell, revised Ānandajoti Bhikkhu, 2021(1880) (2964p), edited, adapted, and added explanations by Ashin Saraṇa.

May you all be happy and healthy,

Ashin Sarana