/Since the Buddha’s time and even until today, monks receive their food from people – they do not have a job that would provide them with a salary. Monks are dependent on the food that people give them. Monks receive food from people mainly in three ways – according to the first way, monks go to the village for alms-round, during which they go from house to house and receive people from anyone who wants to give it. Another way is that lay people come to a monastery and invite monks to the lay people’s homes for one complete meal. Monks then go to that home and have a meal only in that one place. The third way is that people bring food to the monastery, and monks eat in the monastery.

In the Buddha’s time, monks had all three options to gain food. But most often, monks went for alms-round or donors invited them to the donors’ houses. Because there were so many monks, sometimes even thousands, it was not easy for lay people to support monks. To ensure that monks get enough food while lay people are still comfortable donating, a monk was assigned to decide which monks would receive food from which houses or donors.

In this story of Jātaka number 5, the Buddha lives in the monastery of Jetavana, and the fully Enlightened venerable monk Dabba, the son of the Malla family, is responsible for deciding which houses and which donors will donate a meal to which monks. The problem was that some donors donated a delicious meal, and some did not donate a delicious meal. Venerable Udāyī was so unfortunate that he was commonly assigned to the donors who did not give a delicious meal.

One day at a meeting of monks, venerable Udāyī complained that only venerable Dabba assigns meals to monks. Therefore, on another day, venerable Udāyī received the duty to assign houses and donors to monks. However, venerable Udāyī was not clever and did not follow the correct procedures. It is a custom to assign high-quality food to elder, experienced monks and the other food to new, inexperienced monks. Venerable Udāyī didn’t know this, and therefore, other monks called him Lāḷudāyī, which means the “Dull-witted Udāyī.”

The Buddha then explained that venerable Udāyī was dull-witted like this also in one of his previous life: “The elder explained it all to the Tathāgata. “Ānanda,” said he, “this is not the only

time when Udāyi by his stupidity has robbed others of their profit; he did just the same thing in bygone times, too.””/

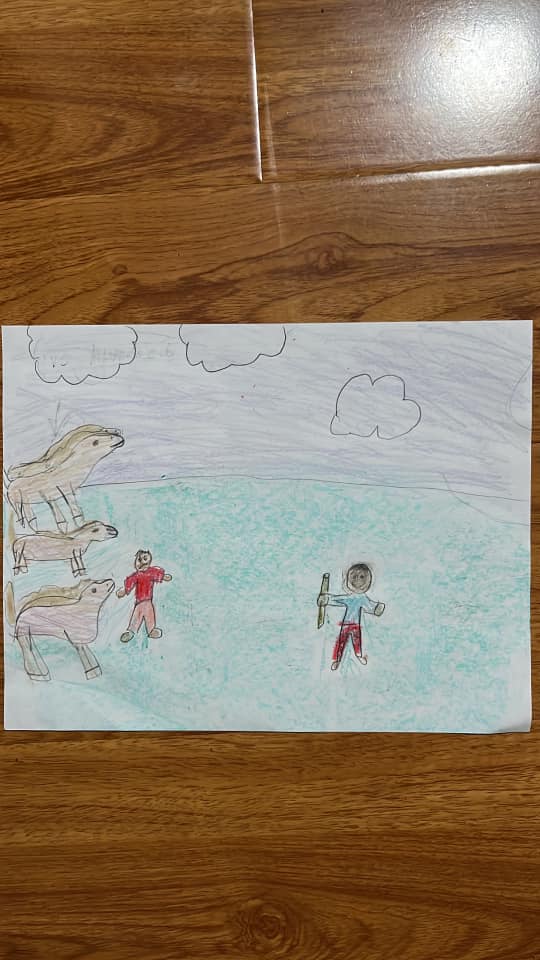

In the past Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares in Kāsi. In those days our Bodhisatta [the Buddha-to-be] was his valuer. He used to value horses, elephants, and the like; and jewels, gold, and the like; and he used to pay over to the owners of the goods the proper price, as he fixed it. But the king was greedy and his greed suggested to him this thought: “This valuer with his style of valuing will soon exhaust all the riches in my house; I must get another valuer.” /The king worried that if the valuer is righteous and does not deceive the people who sell their things, the wealth of the king will not increase./ Opening his window and looking out into his courtyard, he noticed walking across a stupid, greedy person in whom he saw a likely candidate for the post. So the king had the man sent for, and asked him whether he could do the work. “Oh yes,” said the man; and so, to safeguard the royal treasure, this stupid fellow was appointed valuer. After this the fool, in valuing elephants and horses and the like, used to fix a price dictated by his own fancy, neglecting their true worth; but, as he was valuer, the price was what he said and no other.

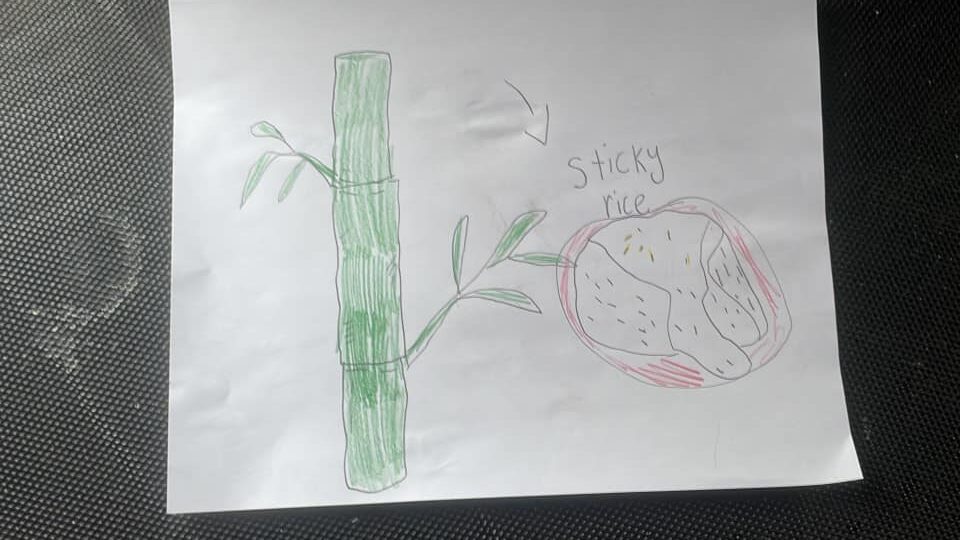

At that time there arrived from the north country a horse-dealer with 500 horses. The king sent for his new valuer and bade him value the horses. And the price he set on the whole 500 horses was just one bamboo tube measure of rice, which he ordered to be paid over to the dealer, directing the horses to be led off to the stable. Away went the horse-dealer to the old valuer, to whom he told what had happened, and asked what was to be done. “Give him a bribe,” said the ex-valuer, “and put this point to him: ‘Knowing as we do that our horses are worth just a single bamboo tube measure of rice, we are curious to learn from you what the precise value of one bamboo tube measure of rice is; could you state its value in the king’s presence?’ If he says he can, then take him before the king; and I too will be there.”

Readily following the Bodhisatta’s advice, the horse-dealer bribed the man and put the question to him. The other, having expressed his ability to value a bamboo tube measure of rice, was promptly taken to the palace, where also went the Bodhisatta and many other ministers. With appropriate respect, the horse-dealer said: “Sire, I do not dispute it that the price of 500 horses is a single bamboo tube measure of rice; but I would ask your majesty to question your valuer as to the value of that measure of rice.” Ignorant of what had passed, the king said to the fellow, “Valuer, what are 500 horses worth?” “A bamboo tube measure of rice, sire,” was the reply. “Very good, my friend; if 500 horses then are worth one bamboo tube measure of rice, what is that measure of rice worth?” “It is worth all Benares and its suburbs,” was the fool’s reply.

(Thus we learn that, having first valued the horses at a bamboo tube measure of hill-paddy to please the king, he was bribed by the horse-dealer to estimate that measure of rice at the worth of all Benares and its suburbs. And that though the walls of Benares were 120 miles round by themselves, while the city and suburbs together were three thousand miles round! Yet the fool priced all this vast city and its suburbs at a single bamboo tube measure of rice!)

Hereupon the ministers clapped their hands and laughed merrily. “We used to think,” they said in scorn, “that the earth and the realm were beyond price; but now we learn that the kingdom of Benares together with its king is only worth a single measure of rice! What talents the valuer has! How has he retained his post so long? But truly the valuer suits our king admirably.” Then the Bodhisatta repeated this verse:

“Do you ask how much a peck of rice is worth?

Why, all Benares, both within and out.

Yet, strange to tell, five hundred horses too

Are worth precisely this same peck of rice!”

Thus put to open shame, the king sent the fool packing, and gave the Bodhisatta the office again. And when his life closed, the Bodhisatta passed away to live another life as he deserved according to the good or bad actions he did in the past.

—

The Buddha narrated this story and made the connection linking both together: the Buddha identified the Jātaka (previous birth) by saying in conclusion, “The Dull-witted Udāyi was the stupid rustic valuer of those days, and I myself the wise valuer.”

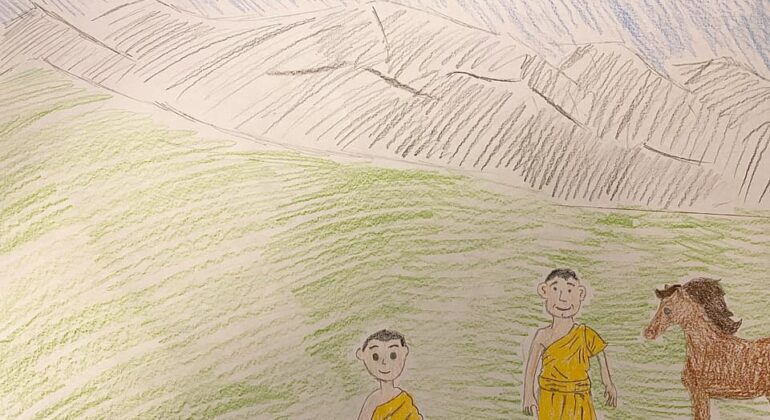

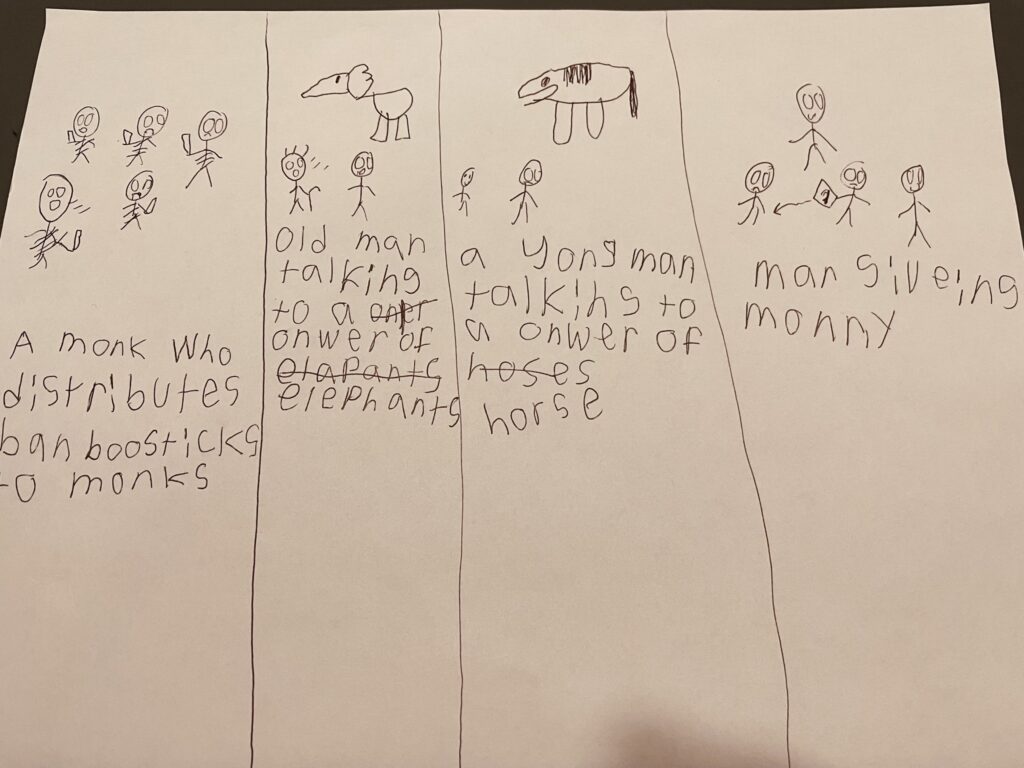

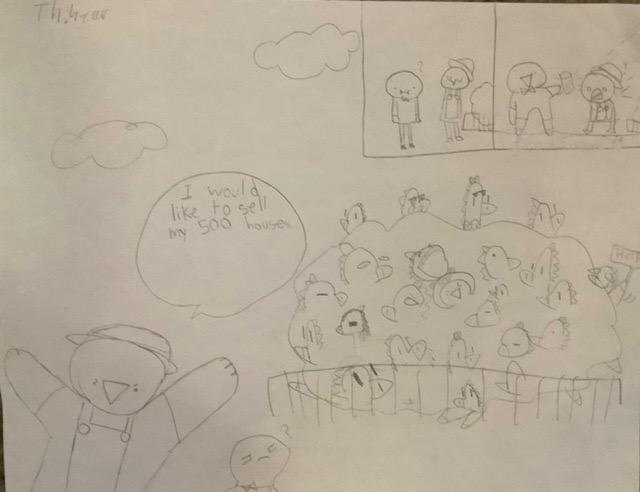

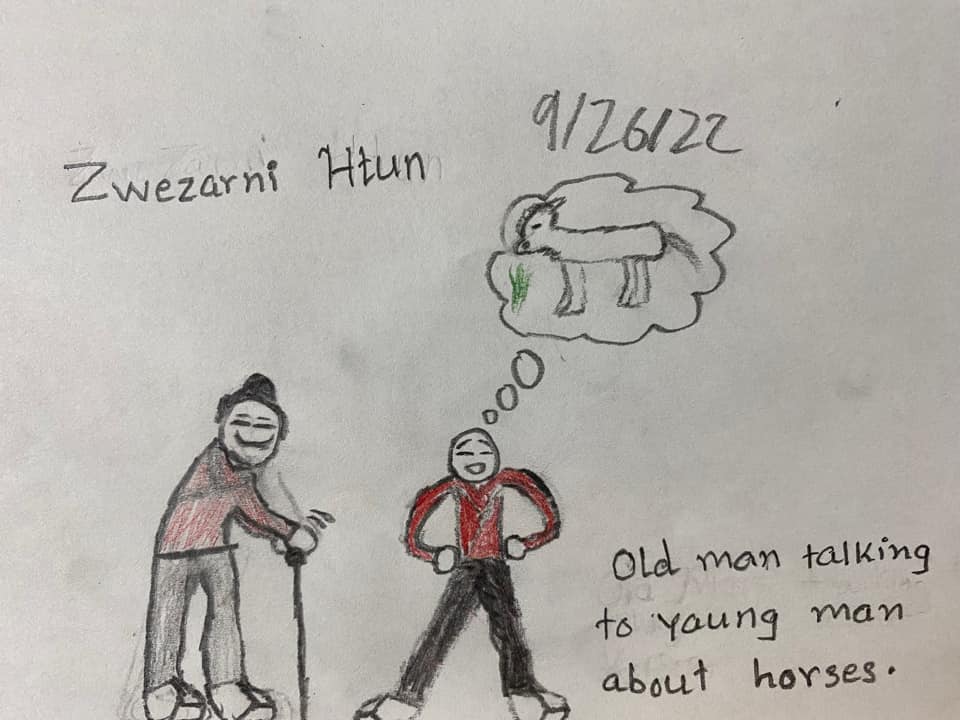

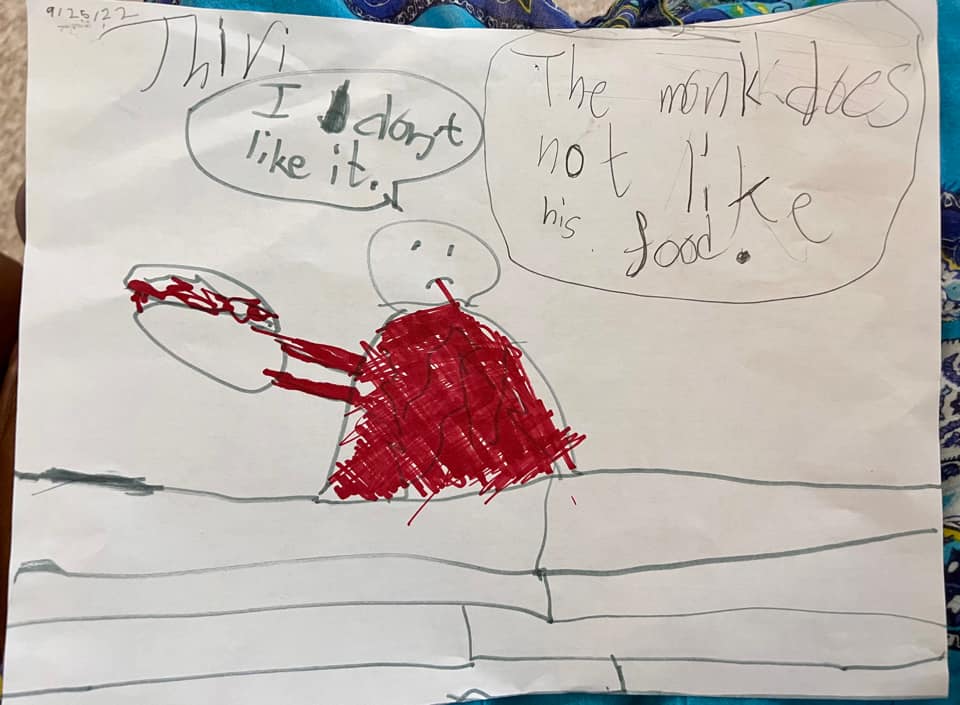

Suggestions for drawing:

A monk who distributes bamboo sticks to monks (the meal-tickets of that time) ; an upset monk who speaks to other monks at a gathering of monks; an old man talking to an owner of elephants; a young man talking to an owner of horses; the king listening to a young man while old men stand around; a wealthy man gives money and bribes a young man; old men laughing; and anything else related to the story.

Picture for inspiration: Myanmar bamboo-tube with sticky rice (ကောက်ညှင်းကျည်တောက်). I am thankful to venerable Hemacitto and Dr. Ko Thaw Zin for these photos.

Jātakas – The Jātaka Translation or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births (pages 169-171) – T.W. Rhys Davids, R. Chalmers, H.T. Francis, W.H.D. Rouse, E.B. Cowell, revised Ānandajoti Bhikkhu, 2021(1880) (2964p). Ashin Saraṇa narrated the story from the Buddha’s time again in simple words, and in the story from a past life, changed archaic words into modern expressions.

May you all be happy and healthy,

Ashin Sarana